Richard Kamler, artist, educator, curator had for 40 years been engaged with creating art that takes as its premise that of social change and cultural transformation. He has received numerous awards for this work, among them a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a Soros Foundation Open Society Artist Fellowship, a California Arts Council Fellowship, and a grant from the Institute for Noetic Sciences. Kamler has exhibited his installations, sound pieces, drawings, sculptures, presentations, actions and events in museums, galleries and public spaces throughout the world.

Our Beloved Richard passed away on November 1, 2017.

He will be sorely missed.

For inquiries about Richard's art, please contact his widow, Joya Cory.

joyacory@gmail.com

415-812-3127

Link to photo gallery of art for sale, click on photo for info re size, materials, dates:https://www.samuelhendersonphotography.com/Richard-Kamler/n-cbW9L6/

Password: kamler

This obituary written by Sam Whiting appeared in the SF Chronicle on Nov 8, 2017

Richard Kamler dies — artist and activist used his works as social protest

Mr. Kamler died on Nov. 1 in the San Francisco home he grew up in. The cause of death was thyroid cancer, which he battled for 12 years, according to his wife, the well-known actress, dancer and teacher Joya Cory. He was one day short of his 82nd birthday.

For 40 years, Mr. Kamler created art intended as a tool for social change through installations, sound pieces, sculpture and drawings. One of his more creative interventions was a protest at San Quentin State Prison on April 20, 1992, the night that executions were to be resumed after the reinstatement of the death penalty. In advance of it, Mr. Kamler went to San Francisco Zoo and recorded the lions roaring. He then organized a small fleet to anchor as close to the shore outside the prison as they could get.

Around midnight, when the execution was scheduled to happen, “The Sound of Lions Roaring” was cranked up loud enough to be heard inside the prison. It continued until the Coast Guard came to arrest him on charges of noise pollution. It was intended as “a mixture of the roar of life and the roar of protest,” said Stephen Vincent, a poet and artist who had known Mr. Kamler since the mid-’70s.

Mr. Kamler also taught art at the San Francisco Art Institute and California College of Arts on his way to the University of San Francisco, where he was a tenured professor. He served as chairman of the fine arts department from 2006-2009.

His last major exhibition was a career retrospective mounted in 2012 at the Thacher Gallery on the USF campus. That show was titled “Celebrating Four Decades of Socially Engaged Art,” and it included pictures of some of his installations and interventions, the art itself being impossible to recreate.

This included photos of the loaf of French bread, 75 feet long and 20 feet tall, that was launched on the bay in 1995. The loaf was towed behind a boat operated by Greenpeace and accompanied by the banner “Make Bread Not Bombs” to protest nuclear weapons tests conducted by France.

“I’ve always been interested in how art can be used to make a difference, politically, socially and culturally, and lead to transformation,” Mr. Kamler told the Chronicle’s Jesse Hamlin at the time of the show.

Born Nov. 2, 1935, Richard Dean Kamler grew up in the Sunset District and attended Lawton Elementary School on 31st Avenue, near his home. He was a graduate of Lowell High School and UC Berkeley, where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture. Upon graduation he served an apprenticeship in New York with Frederick Kiesler, the visionary painter and sculptor.

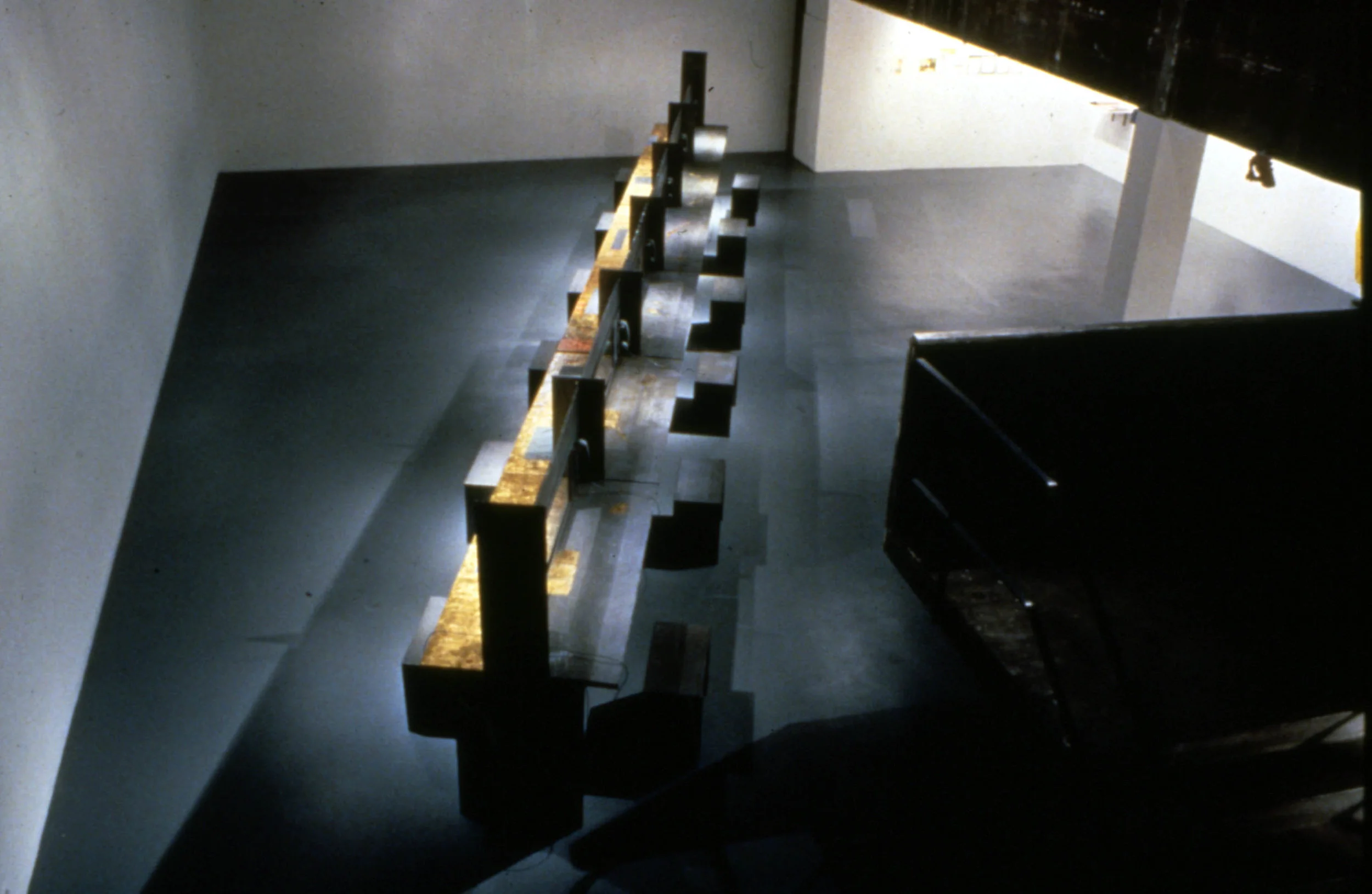

Mr. Kamler’s first major installation was “Out of Holocaust,” a full-size replica of one of the barracks buildings at Auschwitz, plus drawings, done in 1976 at the Judah L. Magnes Museum in Berkeley.

Drawings, photographs and objects from "The Desert Project" installation were exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1979. His work was also shown at the McMullen Museum of Art in Boston, Long Beach Museum of Art and on the grounds of the San Francisco County Jail.

“Richard’s intentions were never to become a blue-chip, gallery artist,” said Vincent. “His life’s work was devoted to re-interpreting the role of the artist as a fully engaged citizen, a legitimate and obligatory member of the public table.”

As such, he became interested in the topics of incarceration and capital punishment. In 1981, Mr. Kamler began a three-year stint as artist in residence at San Quentin. During this time he taped interviews with both inmates and their families, as well as with the families of victims of violent crimes.

This became the audio portion of his best-known piece, “Table of Voices,” (1996-2013). He set up a replica of a prison visiting room, with phones on either side of a divider. Visitors on one side of the partition could pick up the phones and hear the real stories of the victims, as told by family members. On the other side they could hear the stories of the convicted, often expressing remorse.

“Table of Voices” was installed at Alcatraz and later traveled the United States.

For an exhibition called “Maximum Security” at the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art he built two full-size prison cells, each with a maggot-infested lamb carcass rotting in the corner. Patrons examined this through barbed wire.

For an exhibition called “Last Meal” he sculpted out of lead the trays of food that condemned inmates ordered on Death Row in Huntsville, Texas.

Mr. Kamler stayed busy until the end, looking forward to his next show at The Contemporary Jewish Museum of San Francisco. He did not live to see that exhibition.

Survivors include Cory, his wife of 46 years, his son Joshua Cory Kamler and daughter-in-law Celina Kamler, and grandsons Maceo and Carmelo Kamler, all of Alameda.